Voter suppression makes the racist and anti-worker Southern model possible: Rooted in Racism and Economic Exploitation: Spotlight

Summary: From the abolition of slavery until now, Southern white elites have used a slew of tactics to suppress Black political power and secure their economic interests—including violence, voter suppression, gerrymandering, felony disenfranchisement, and local preemption laws.

Black voter disenfranchisement remains a key feature of the racist and anti-worker Southern economic development model today. However, periods of progress toward Black political empowerment, such as during Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement—though met with fierce suppression—show that targeted policy action has the power to dismantle racist barriers to political participation and disrupt the cycle of political suppression and economic exploitation. While significant advances have been made over the last century, a resurgent backlash underscores the need to strengthen civil rights protections and ensure all Southern workers and their families can enjoy political and economic equality.

There is a long strand of history connecting the legacy of slavery to the political and economic landscape of the Southern United States today. As EPI’s Rooted in Racism series has shown, the Southern economic development model is characterized by low wages, regressive taxes, few regulations on businesses, few labor protections, a weak safety net, and fierce opposition to unions. Just like the antebellum South’s economy was built on the exploitation of enslaved labor, today’s Southern economy also relies on a disempowered and precarious workforce (Childers 2024b). This spotlight examines how political and economic suppression—dynamics in the South which are rooted in racism—have played a central role in creating and maintaining the Southern economic development model.

Since the first enslaved Africans arrived in the Americas, authoritarian, white supremacist forces have used disenfranchisement, fraud, intimidation, and violence to extract wealth from Black and brown populations (Desmond 2019; Torres-Spelliscy 2019). While the abolition of slavery after the Civil War briefly disrupted this dynamic, repression quickly reemerged in new forms. In backlash against Black emancipation and enfranchisement, Southern leaders adopted Black Codes and later Jim Crow laws to entrench white supremacy and maintain an economy predicated on exploitation. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s was a lurch forward for racial equity and Black political power. However, these advances have been met with renewed backlash. The dismantling of key protections under the Voting Rights Act of 1965—particularly via the 2013 Shelby v. Holder decision—have fueled a resurgence of voter suppression tactics that harken back to the post-Reconstruction efforts to disenfranchise Black Americans. Today, as in the past, these efforts aim to undermine racial equality and perpetuate the Southern economic development model.

How emancipation and Reconstruction defined Black citizenship and civic engagement

The Declaration of Independence proclaimed that all men were created equal, with unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Yet these ideals coexisted alongside brutal chattel slavery. As Figure A shows, nearly one-fifth to one-eighth of the U.S. population—enslaved Africans and Black Americans—were systematically denied these rights (Gibson and Jung 2002). For nearly a century after the nation’s founding, the U.S.—and the Southern economy in particular—thrived on this exploitation, building immense wealth through the forced labor of enslaved people.

Nearly one-fifth to one-eighth of the U.S. population—enslaved Africans and Black Americans—lived under brutal chattel slavery: Slaves as a share of the U.S. population, 1790–1860

| Year | Slaves as a share of U.S. population |

|---|---|

| 1790 | 17.8% |

| 1800 | 16.8% |

| 1810 | 16.5% |

| 1820 | 16.0% |

| 1830 | 15.6% |

| 1840 | 14.6% |

| 1850 | 13.8% |

| 1860 | 12.6% |

Source: Gibson and Jung 2002, Table 1.

Throughout U.S. history, Black Americans have had to fight to secure their right to self-determination and political representation. Prior to emancipation, only five Northern states—Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont—granted some degree of Black suffrage, but their Black voters still faced widespread discrimination (Litwack 1965). In 1857, the Supreme Court further undermined Black citizenship with its infamous Dred Scott v. Sandford ruling, which declared that Black people, whether enslaved or free, were neither citizens nor entitled to protections under the Constitution of the United States. This decision exacerbated tensions around the topic of slavery that ultimately precipitated the Civil War.

Although the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865 marked the formal end of slavery, it did not result in true liberty or self-determination for Black Americans. Within months of Robert E. Lee’s surrender to Union General Ulysses S. Grant on April 9, 1865, acrimonious white Southerners, who feared the loss of political and economic dominance, quickly mobilized to resist Black emancipation and enfranchisement.

Starting with Mississippi and South Carolina in 1865, Southern state governments became instruments for reestablishing the exploitative system of plantation labor after the Civil War. These states enacted laws known as Black Codes, which criminalized virtually all aspects of Black life. These laws required freed men, women, and children to sign exploitative labor contracts, often on the very plantations where they had been enslaved (EJI n.d.d). Black Codes also criminalized unemployment through vagrancy laws, which served to coerce freed persons into these labor contracts. Individuals who were unfortunate enough to be caught up in the web of criminalization were often funneled into prison labor systems, which leased convicted laborers out to private businesses for profit. By 1869, most former Confederate states—including Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, South Carolina and Texas—had adopted such prison labor schemes (Kelley 2017; Cardon 2017; Dirkson 2024; EJI n.d.c).

Black Codes also curtailed the civic rights of Black Americans by prohibiting them from testifying against white individuals in court, serving on juries, joining militias, or exercising their right to vote. As renowned sociologist and founder of the NAACP W.E.B. Du Bois (1935) observed, these laws were “an indisputable attempt on the part of Southern states to make Negros slaves in everything but name.” Black Codes were a direct effort to maintain white supremacy through political and economic control of the post-emancipation South.

The conditions for Black men and women in the South under Black Codes were so dire, they were likened to a “slow-motion genocide” (Gordon-Reed 2011; PBS n.d.a; USCS 1865). Reports on the situation in the South galvanized Republicans in Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866, overriding President Andrew Johnson’s veto. This was the first federal law to define U.S. citizenship and affirm that all citizens, regardless of race, were entitled to equal protection under the law. This also laid the groundwork for the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, which placed Southern states under military rule to enforce these new rights and overcome the recalcitrance of the former Confederate states.

Ratified in 1868, the 14th Amendment further guaranteed equal protection for all citizens and redefined citizenship to include Black Americans. In 1870, the 15th Amendment was adopted, which prohibited denying the right to vote based on race, color, or previous condition of servitude. Through these reforms, millions of formerly enslaved Black men were enfranchised.

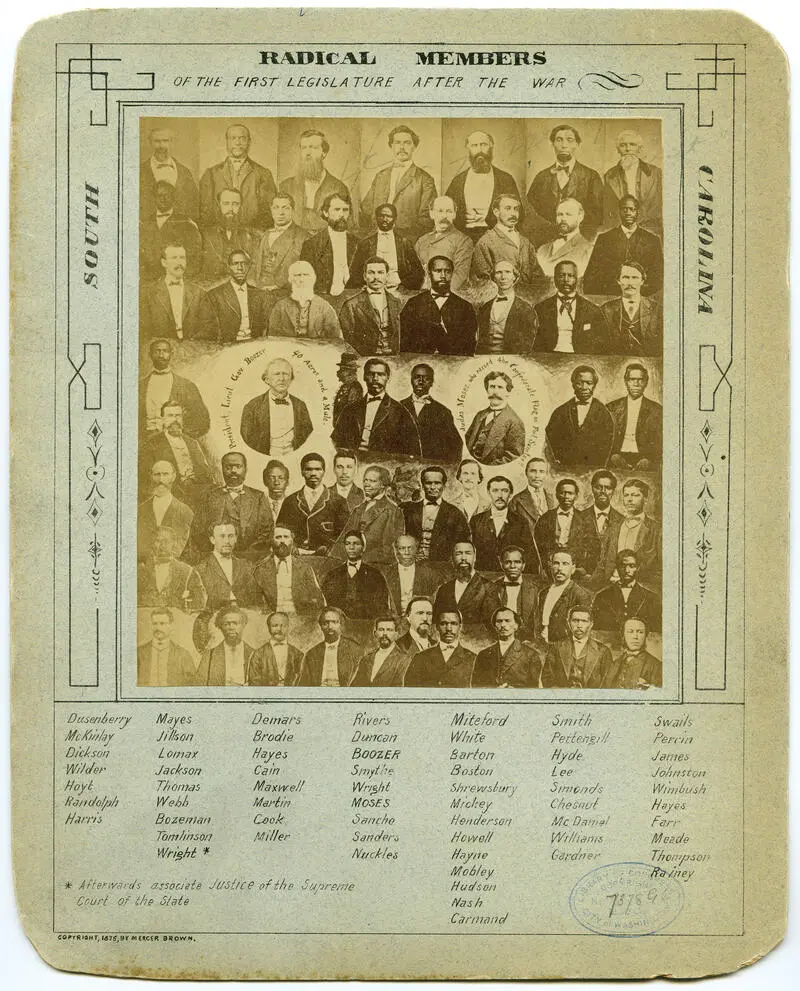

Figure B. A photograph of the 1868 legislature of South Carolina—the first state legislature with a Black majority (Library of Congress 1876).

Under Reconstruction, Black civil engagement flourished. Shown in Figure C, Black men registered to vote for the first time in staggering numbers and achieved outright majorities of registered voters in five of the former Confederate states. These new, multiracial electorates drew up new state constitutions, eliminating many of the barriers to voting established by the Black Codes. During this period, around 703,400 of the roughly four million freed men and women registered to vote (Franklin 1994; Census 1870). Additionally, 660,000 white Southerners who had pledged the Ironclad Oath— swearing loyalty to the Union—registered to vote. By 1870, Mississippi sent the first Black U.S. Senator, Hiram Revels, to Washington D.C. (MCRM 2024). During this period, around 1,500 to 2,000 Black individuals were elected at every level of public office across the South (Foner 1993).

Black civic engagement flourished during Reconstruction: Composition of registered voters in select Southern states, by race, 1868

| State | White registration | Black registration |

|---|---|---|

| Louisiana | 35% | 65% |

| South Carolina | 37% | 63% |

| Alabama | 37% | 63% |

| Florida | 43% | 57% |

| Mississippi | 43% | 57% |

| Georgia | 50% | 50% |

| Virginia | 53% | 47% |

| Texas | 55% | 45% |

| North Carolina | 59% | 41% |

| Arkansas | 61% | 39% |

Notes: Registration data refer to men aged 21+. Figures for Arkansas and Mississippi are estimates since no demographic data were collected by the Union army’s Fourth Military District.

Jim Crow, the birth of modern voter suppression, and the Southern model

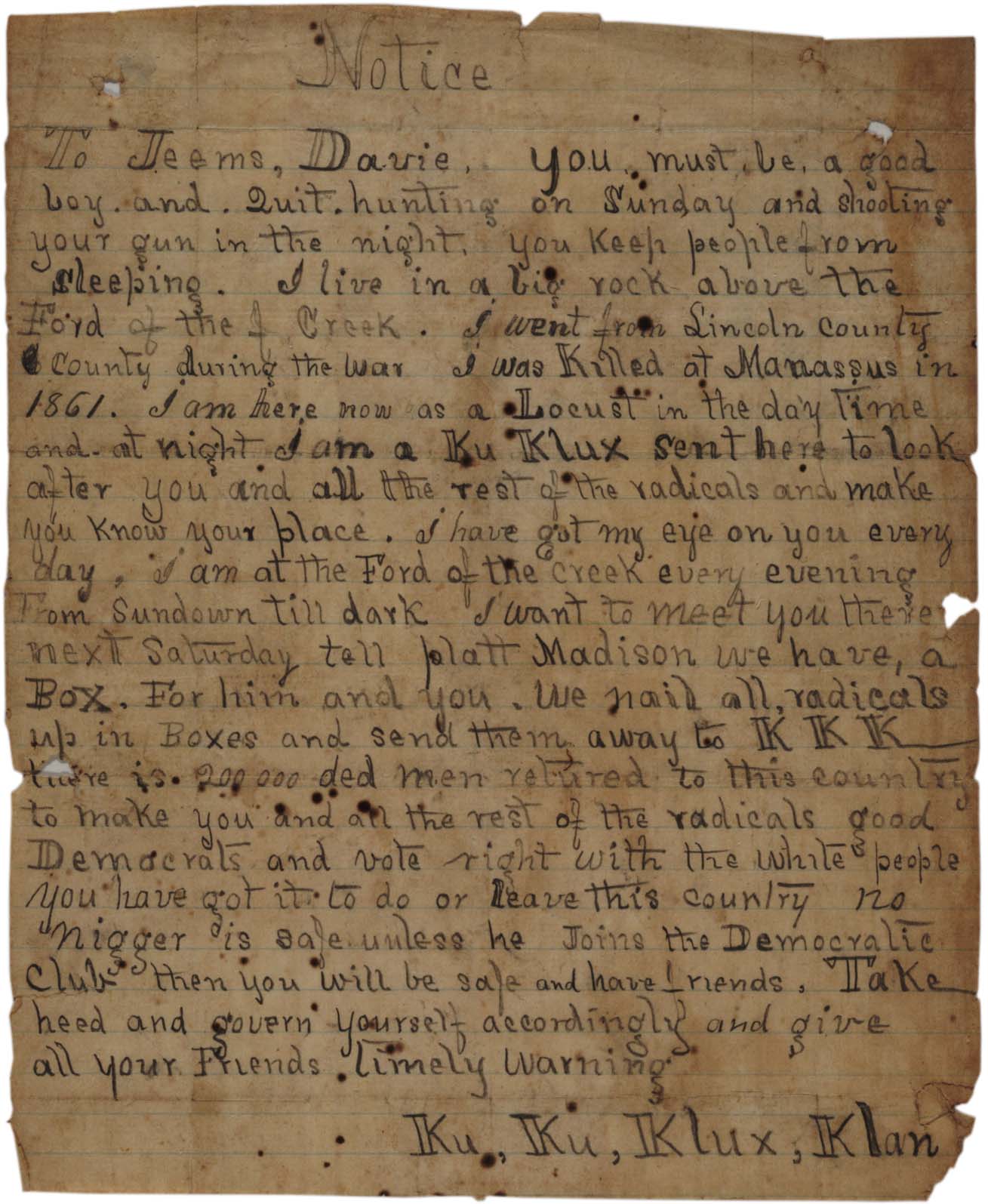

The rapid progress made during Reconstruction quickly met a violent backlash, with Jim Crow laws ushering in a new era of racialized political suppression and entrenchment of the Southern model. White supremacist groups, intent on reclaiming their power, used any means at their disposal—violence, intimidation, and legal manipulation—to reverse the gains made by Black Americans. One report by the Equal Justice Initiative conservatively estimates that 2,000 lynchings took place between 1865–1876, many with impunity (EJI 2020). The impact of lynching as an act of voter suppression historically shows up in the present: Data show that Black people who live in Southern counties that experienced more lynchings in the past are less likely to register to vote today (Williams 2020).

In 1876, a compromise between the Republican and Democratic parties to elect Rutherford B. Hayes in exchange for the removal of Union troops from the South marked what many consider the end of Reconstruction (Waxman 2022). With this concession, white supremacist violence accelerated and many Southern governments were recaptured by Confederate loyalists (EJI n.d.a).

Figure D. A letter of warning from the Ku Klux Klan, addressed to Davie Jeems, a Black Republican elected sheriff in Lincoln County, Georgia in 1868 (Darling 2024, Gilder Lehrman Institute).

Amid a renewed campaign of white terrorism, newly empowered Southern legislators adopted a barrage of laws to institutionalize racial segregation and disenfranchise Black voters. This period, commonly referred to as the Jim Crow era, was the genesis of many of the modern tactics of voter suppression. Although the 15th amendment prohibited laws that denied the right to vote according to race, color, or previous condition of servitude, white supremacist legislators circumvented these protections by devising “race-neutral” laws—like poll taxes, literacy tests, tests of moral character, and disenfranchisement via criminal conviction. Since many of these barriers also impacted poor whites, legislators adopted grandfather clauses that exempted whites from these laws if their grandfathers had been eligible to vote before 1867.

In 1890, Mississippi legislators convened a constitutional convention with the explicit aim of disenfranchising Black voters. The convention’s President, Solomon Saladin Calhoon, said: “Let us tell the truth if it bursts the bottom of the Universe … We came here to exclude the negro. Nothing short of this will answer” (Shafer 2021). By the convention’s end, legislators had imposed a $2 poll tax, literacy tests, and disenfranchisement as a penalty for nine crimes that they believed Black people would be more likely to be convicted of than white people (MDAH 2024). By 1892, Black voter registration in Mississippi plummeted from 66.9% in 1867 to just 5.7% (MCRM 2024; Hannah et al. 1965).

Similar scenarios played out across the South:

- In 1898, Louisiana adopted a constitution with such extensive restrictions that an estimated 25% of the white male population would have been disqualified without the grandfather clause. Under this constitution, the number of registered Black voters plummeted from 130,000 to just 1,718 by 1904.

- By 1883, only 3,700 Black Alabamans were registered to vote, down from a peak of 140,000.

- By 1898, just 2,800 Black South Carolinians were registered to vote, down from 92,000 in 1876.

- Between 1920 and 1930, only about 10,000 Black Georgians registered to vote out of a total Black electorate of 370,000 (Lewis and Allen 1972; EJI 2024b).

By the turn of the 20th century, Black Southerners endured conditions that starkly resembled the brutality of slavery while lacking the political power to challenge or change their circumstances. Vagrancy laws and convict leasing programs functioned as slave trafficking networks, ensnaring thousands of Black men and women on fabricated charges, forcing them into grueling labor under conditions often as harsh as those of slavery (Blackmon 2009). In 1896, the Supreme Court dealt a further blow to racial equality by upholding the constitutionality of racial segregation under the “separate but equal doctrine” in Plessy v. Ferguson. Every place, from barbershops to hospitals, were racially segregated (EJI 2018). White supremacist forces, working across all levels of government, collaborated to reestablish and maintain racial hierarchy.

Southern elites respond to the Great Migration North

The oppressive conditions of the South, combined with a surge in labor demand in Northern cities during the World Wars, ignited the Great Migration. Initially, many Southern whites celebrated the exodus of Black residents. However, as it became clear that the northward emigration of Black laborers posed a threat to the economic development model in the region, Southern elites changed their disposition (Willis 2019). Southern states responded by banning newspapers from advertising jobs in the North, arresting Northern labor recruiters, and even detaining Black residents to prevent them from boarding northbound trains. Some white Southerners even interfered with the U.S. mail to disrupt the distribution of certain newspapers that advertised jobs in the North (Clark 2024a).

Despite these efforts to stymie the Great Migration, approximately six million Black Americans fled the South’s racism and violence between 1910 and 1970 in search of better opportunities and safety. Over this period, the share of the U.S. Black population residing in the South fell from 90% to 53% (Frey 2022).

Progressive policies of the New Deal era—such as the abolition of brutal convict leasing systems; the new Fair Labor Standards Act, which established a minimum wage and the 40-hour work week; and the National Industrial Recovery (NIRA) and the National Labor Relations Acts (NLRA), which enshrined the right to join a union and collectively bargain—ushered in economic gains for working class Americans.

Though many benefitted from the New Deal’s economic programs, prosperity was not universal. Racism and the failure to address systemic inequalities excluded many Black workers from New Deal era policies (Payne-Patterson and Maye 2023). Nevertheless, conditions for Black workers outside of the South were markedly better than those of their Southern counterparts. By 1940, Black Southerners who moved North were earning double the amount earned by their counterparts who remained in the South (Boustan 2016).

Some of the improved conditions for Black workers who migrated North can be attributed to the growth of the labor movement and its ability to raise standards across industries. Between 1933 and 1945, union membership grew 252%; union members accounted for 9.5% of the workforce in 1933 and 33.4% in 1945 (EPI 2021). Unfortunately, racist carve-outs in the NLRA denied many Black and brown agricultural and domestic workers the federally protected right to collectively bargain. Black workers were often excluded from more lucrative jobs in the defense manufacturing industry. Additionally, many Black workers faced prejudice within predominantly white unions or were even excluded from joining unions altogether (NUL 1930). However, as the union movement grew, labor unions recognized that raising Southern labor standards was key to raising labor standards nationwide. In 1946, the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) launched Operation Dixie, a campaign to unionize Southern workers and challenge exploitative labor practices in the region.

White Southern elites recognized that a powerful Southern labor movement posed a dual threat: First, it would threaten the Southern economic development model by forcing employers to raise pay and improve working conditions; and second, it would create vehicles for cross-racial solidarity that could undermine the political dominance of white Southern elites. In response, Southern states enacted so-called right-to-work (RTW) laws that were explicitly designed to undermine collective bargaining and prevent cross-racial solidarity (Childers, Kamper, and Sherer 2024).

This fierce opposition to worker organizing continues today. In 2024, when workers at a Mercedez-Benz auto manufacturing plant petitioned to join the United Auto Workers union, Alabama Governor Kay Ivey denounced the unionization effort, claiming that the state’s “model for economic success is under attack” (Thornton 2024). Ivey, along with the governors of Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas, further issued a joint statement opposing the unionization campaign (OGSAL 2024). Notably, many of these same RTW states also have some of the most restrictive voting laws, low minimum wages, and other policies that aim to undercut worker power (Maye 2022).

The Civil Rights Movement, a Second Reconstruction

Throughout the 20th century, it became increasingly clear that securing equal rights for Black Americans was critical to dismantling the Southern model. The Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, often referred to as a Second Reconstruction, directly challenged systemic barriers from the Jim Crow era.

Civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. recognized that ending segregation, expanding voting rights, and securing economic opportunities for all Americans were interconnected struggles, and that the Southern model sustained itself from the political disempowerment of Black people. In a speech at the AFL-CIO convention in 1961 (UMD 2016), he remarked:

“This unity of purpose is not an historical coincident. Negroes are almost entirely a working people. There are pitifully few Negro millionaires and few Negro employers. Our needs are identical with labor’s needs: decent wages, fair working conditions, livable housing, old-age security, health and welfare measures, conditions in which families can grow, have education for their children and respect in the community.

That is why Negroes support labor’s demands and fight laws which curb labor. That is why the labor-hater and labor-baiter is virtually always a twin-headed creature, spewing anti-Negro epithets from one mouth and anti-labor propaganda from the other mouth.”

Just four years after Dr. King’s speech to the AFL-CIO, a watershed moment came when young Black civil rights activists, led by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee organized a 54-mile march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. This march sought to spotlight the violence, beatings, firebombings, and murders targeting those organizing to register Black voters across the South—including the infamous 1965 Mississippi Burning murders, in which civil rights activists Andrew Goodman, James Earl Chaney, and Michael Henry Schwerner were brutally killed (PBS n.d.b). On March 7, 1965—a date known as Bloody Sunday—state troopers brutally attacked peaceful marchers as they crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Shocking images of the attack galvanized President Lyndon B. Johnson and Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965 (Coleman 2015).

The VRA, one of the most consequential voting reforms of the century, remapped power across the South by outlawing many of the post-Reconstruction and Jim Crow era laws that retaliated against increased Black political participation, including poll taxes and discriminatory literacy or moral character tests. Additionally, Section 5 of the VRA required states and jurisdictions with a history of discrimination to preclear any voting law changes with the federal government, which ended the incessant adoption of new “race-neutral” voting restrictions. The VRA also authorized the Department of Justice to appoint election examiners to enforce the guarantee of the 15th Amendment (USCCR 1968).

Just like the Reconstruction Acts of 1867, the impact of the 1965 Voting Rights Act on Black political participation was sudden and significant. Figure E illustrates the dramatic rise in Black voter registration across the South between March 1965 and September 1967. The states with the largest Black voter registration gaps before and after the Voting Rights Act—a proxy for where political suppression was most fierce—are Mississippi (+53.1 percentage points), Alabama (+32.3), Louisiana (+27.3), and Georgia (+25.2). These are the same states that today perform the worst economically; they have low wages, low GDPs, and higher rates of poverty (Childers 2023, 2024a).

Southern Black voter registration saw a dramatic rise between 1965–1967: Black voter registration in select Southern states before and after the Voting Rights Act of 1965

| Voter registration before the Voting Rights Act (March 1965) | Voter registration after the Voting Rights Act (September 1967) | |

|---|---|---|

| South Carolina | 37.3% | 51.2% |

| North Carolina | 46.8% | 51.3% |

| Alabama | 19.3% | 51.6% |

| Georgia | 27.4% | 52.6% |

| Virginia | 38.3% | 55.6% |

| Louisiana | 31.6% | 58.9% |

| Mississippi | 6.7% | 59.8% |

| Texas | 53.1% | 61.6% |

| Arkansas | 40.4% | 62.8% |

| Florida | 51.2% | 63.6% |

| Tennessee | 69.5% | 71.7% |

Source: U.S. Commission on Civil Rights 2018. Adapted from Maye 2022.

Political suppression and the Southern economic development model in the 21st century

The advancements secured by the Civil Rights Movement and the Voting Rights Act achieved a milestone in 2008, when U.S. voters elected the first Black President, Barack Obama. However, this historic election was followed by racist backlash, giving rise to conspiracy theories like the “birther movement,” which alleged the President was not a U.S. citizen (Samuel 2016; Beaumont 2016). It also coincided with new efforts to undermine voting rights. In 2010, Shelby County, Alabama, filed suit in federal court to declare Section 5 of the VRA unconstitutional. Figure F maps states and localities that were required, under Section 5, to preclear any changes to election laws with the federal government due to their history of discrimination.

States with a history of discrimination required to preclear changes to election laws before 2013: States covered by Section 5 of the 1965 Voting Rights Act at the time of the Shelby v. Holder decision

| State | Key | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama | 1 | State covered as whole by Section 5 |

| Alaska | 1 | State covered as whole by Section 5 |

| Arizona | 1 | State covered as whole by Section 5 |

| Arkansas | 0 | |

| California | 2 | Some counties covered by Section 5 |

| Colorado | 0 | |

| Connecticut | 0 | |

| Delaware | 0 | |

| Florida | 2 | Some counties covered by Section 5 |

| Georgia | 1 | State covered as whole by Section 5 |

| Hawaii | 0 | |

| Idaho | 0 | |

| Illinois | 0 | |

| Indiana | 0 | |

| Iowa | 0 | |

| Kansas | 0 | |

| Kentucky | 0 | |

| Louisiana | 1 | State covered as whole by Section 5 |

| Maine | 0 | |

| Maryland | 0 | |

| Massachusetts | 0 | |

| Michigan | 3 | Some townships covered by Section 5 |

| Minnesota | 0 | |

| Mississippi | 1 | State covered as whole by Section 5 |

| Missouri | 0 | |

| Montana | 0 | |

| Nebraska | 0 | |

| Nevada | 0 | |

| New Hampshire | 3 | Some townships covered by Section 5 |

| New Jersey | 0 | |

| New Mexico | 0 | |

| New York | 2 | Some counties covered by Section 5 |

| North Carolina | 2 | Some counties covered by Section 5 |

| North Dakota | 0 | |

| Ohio | 0 | |

| Oklahoma | 0 | |

| Oregon | 0 | |

| Pennsylvania | 0 | |

| Rhode Island | 0 | |

| South Carolina | 1 | State covered as whole by Section 5 |

| South Dakota | 2 | Some counties covered by Section 5 |

| Tennessee | 0 | |

| Texas | 1 | State covered as whole by Section 5 |

| Utah | 0 | |

| Vermont | 0 | |

| Virginia | 1 | State covered as whole by Section 5 |

| Washington | 0 | |

| Washington D.C. | 0 | |

| West Virginia | 0 | |

| Wisconsin | 0 | |

| Wyoming | 0 |

Source: U.S. Department of Justice data compiled by Li 2024.

In June 2013, the Supreme Court ruled in Shelby v. Holder that Section 4(b) of the VRA—which outlined the formula used to determine which jurisdictions were subject to preclearance—was unconstitutional because it had been established based on electoral conditions of the 1960s and 1970s (Li 2024). While Section 5 remained intact, it became nullified in practice without a formula to determine which states are subject to preclearance. In 2022, Congress attempted to ratify a new preclearance formula, as part of a voting reform package called the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. This bill was ultimately thwarted by a filibuster by Senate Republicans (Hulse 2022).

Political suppression in the post-Shelby v. Holder era

The strategies employed by anti-democratic lawmakers to make voting more difficult for Black and brown citizens have continually evolved, particularly in the post-Shelby v. Holder era. Nullifying preclearance protections under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 led to the proliferation of restrictive voting laws across the South. Between 2013 and 2023, at least 29 states passed 94 restrictive voting laws in a widespread and coordinated effort to limit Black and brown voting access (Singh and Carter 2023).

Some of the most common tactics employed by states include eliminating same-day voter registration, reducing early voting periods, removing polling places, creating mechanisms for overruling local election officials, “purging” voters from registration lists, and creating harsh and expansive penalties for seemingly mundane administrative errors (Berzon and Corasantini 2024; Levine 2024; LCEF 2019; Clark 2024b; Vasilogambros 2024). Although done under the guise of preserving “election integrity” or responding to budget constraints, the effect (and intent) of these tactics is clearly to make it harder for Black and brown citizens to vote. A 2022 study showed that voters from Black neighborhoods waited 29% longer and were 74% more likely to spend more than 30 minutes at their polling place compared with voters from white neighborhoods (Chen et al. 2022).

In recent years, politicians have also taken aim at the credibility of the electoral system by making claims of widespread voter fraud. Following the expansion of vote-by-mail during the COVID-19 pandemic, some politicians, including former President Donald Trump, made claims that non-citizens, deceased, or out-of-state voters were casting ballots and alleged that individuals were voting multiple times (Trump 2020; Domonoske 2017). Despite the lack of evidence for these claims, states are increasingly adopting harsh penalties for perceived election interference, while restricting voting access and criminalizing acts like providing food or water to voters in line (Democracy Now 2022; Fowler 2021; Ura 2021). This coordinated effort to undermine confidence in the country’s elections has been effective: In 2020, just 59% Americans expressed confidence that their votes would be accurately cast and counted, down from 70% in 2018 (McCarthy 2020).

In aggregate, these restrictive voting laws appear to have been successful in hampering and/or discouraging voter turnout among Black voters, relative to their white peers. Figure G documents the reemergence of a Black-white voting gap in the South following the Shelby v. Holder ruling. In 1964, Southern Black voter turnout trailed that of white voters by 16 percentage points in presidential election years. When U.S. voters elected the first Black president in 2008, Southern Black voters nearly closed the gap, trailing white voters by just half a percentage point. And in 2012, for the first time on record, Black voters outperformed white voters by two percentage points. But the trend reversed following the Shelby v. Holder ruling and Black voters underperformed white voters by 4.4 points in 2016, and 8.6 points in 2020.

The Black-white voting gap has reemerged in the years following Shelby v. Holder: Reported voting rates of the Southern voting-age population in presidential election years by race and ethnicity, 1964–2020

| White | White non-Hispanic | Black | Asian and Pacific Islander | Hispanic (of any race) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | 59.5% | 44.0% | |||

| 1968 | 61.9% | 51.6% | |||

| 1972 | 57.0% | 47.8% | |||

| 1976 | 57.1% | 57.1% | 45.7% | ||

| 1980 | 59.2% | 48.2% | 30.1% | ||

| 1984 | 59.8% | 53.2% | 32.4% | ||

| 1988 | 58.5% | 48.0% | 32.9% | ||

| 1992 | 63.6% | 54.3% | 24.5% | 32.0% | |

| 1996 | 56.7% | 50.0% | 22.6% | 27.6% | |

| 2000 | 58.2% | 53.9% | 22.2% | 28.7% | |

| 2004 | 62.8% | 55.9% | 25.7% | 27.6% | |

| 2008 | 63.4% | 62.9% | 25.4% | 30.0% | |

| 2012 | 61.1% | 63.1% | 28.2% | 30.0% | |

| 2016 | 62.1% | 57.7% | 32.0% | 30.5% | |

| 2020 | 67.6% | 59.0% | 42.2% | 36.0% |

Notes: Composite series of white non-Hispanic voters includes white voters of any ethnicity from 1964–1976. Black voter series includes other races in 1964. Prior to 1972, data refer to people aged 21–24, with the exception of those aged 18–24 in Georgia and Kentucky, 19–24 in Alaska, and 20–24 in Hawaii.

Source: EPI analysis of U.S. Census Bureau 2024, Current Population Survey data, Table A9.

Discriminatory redistricting and representation

Gerrymandering, the manipulation of congressional redistricting for political gain, is another tactic that has long undermined the democratic process—particularly in the South, where it has been used to entrench white political power. Redistricting, the process of creating geographic boundaries of electoral districts, typically occurs every decade following the release of the Census. Since the founding of the United States, political parties vying for power frequently gamed the redistricting process to secure an electoral advantage (Engstrom 2013). And following emancipation and Black suffrage, Southern legislators regularly used discriminatory redistricting to suppress Black and brown voting power.

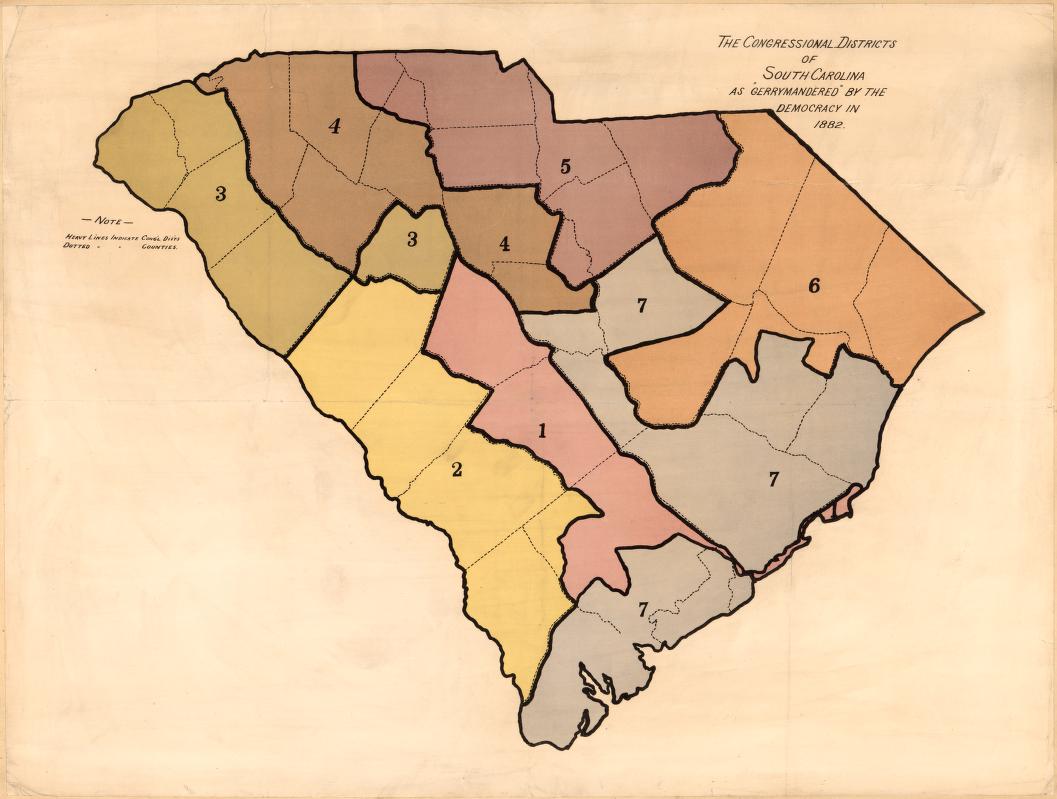

One of the most glaring historical examples of discriminatory racial gerrymandering is South Carolina’s 1882 “boa constrictor” district map, which created discontinuous boundaries, and aimed to stifle Black voter power by concentrating the state’s Black population into one district (LOC 1882).

Figure H. South Carolina’s 1882 “boa constrictor” congressional district map, which packed Black voters into one noncontiguous district (District 7) and diluted their power in all other districts. (LOC 1882)

The VRA of 1965 gave individuals the power to legally challenge racial gerrymanders. But to this day, Southern states continuously engage in discriminatory gerrymandering under the guise of partisan redistricting. Below are just a few examples of racial gerrymandering cases from recent years:

- In 2016, a federal court struck down North Carolina’s congressional map, ruling it an unconstitutional racial gerrymander aimed at diminishing the voting power of Black Americans.

- In 2017, a federal court ruled that several Texas congressional and state legislative districts were drawn with the intent of discriminating against Black and Latino voters.

- In 2020, South Carolina’s congressional map was deemed illegal by a federal court. An amicus brief alleged that South Carolina had purposefully drawn discriminatory districts that “bleached” Black voters out of select congressional districts in a manner that harkened back to the 1882 “boa constrictor” congressional district map. This ruling was later overturned by the Supreme Court in 2023.

- In 2022, a federal court struck down Alabama’s congressional map for diluting Black voters’ political influence by spreading them across multiple districts. After defying an order to create a second Black majority district, litigation in this case is ongoing (Li 2023).

Partisan actors have also attempted to manipulate the apportionment process by proposing changes to the way the population is counted (Rudensky et al. 2021). These efforts included proposals to add a citizenship question to the Census and to not count non-voting populations in apportionment. Experts predict that this approach would disproportionally target Latino communities (as well as Asian American and Black communities, to a lesser extent), which would clearly be a violation of the Census Act (Rudensky et al. 2021).

Despite the safeguards of the VRA, particularly Section 2 which prohibits voting practices with discriminatory effects, gerrymandering continues to undermine Black and brown voting power across the South.

Mass incarceration is a key tool for disenfranchising Black and brown voters

Felony disenfranchisement is a vestige of the racist backlash against emancipation and Reconstruction and remains a pervasive tool for suppressing Black and brown political participation in the South today. As Black Code laws laid the groundwork for mass incarceration by criminalizing Black freed men and women, states also enacted laws to strip voting rights from people convicted of felonies. Between 1865 and 1880, 13 states (Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Illinois, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas) either introduced or expanded felony disenfranchisement laws. Even as the VRA of 1965 undid many of the barriers to voting established by Black Codes and Jim Crow laws, 25 states still have some form of felony disenfranchisement in place (Brennan Center n.d.).

In recent years, states have increasingly prosecuted individuals for voting without realizing they were disenfranchised due to a felony conviction. In 2018, Florida voters passed Amendment 4 to reinstate voting rights to individuals with previous felony convictions. Florida Governor Ron DeSantis and the Florida legislature responded by passing Senate Bill 7066, which prohibited individuals with previous convictions from voting until they paid court-imposed fees (Brennan Center 2023). In 2022, footage was released showing individuals being arrested at gunpoint and charged with election fraud after having unknowingly voted without paying these court-ordered fees (Mower 2022).

Today, about 4.4 million Americans, roughly the equivalent of the entire voting population of the state of Minnesota, have their right to vote revoked because of a criminal conviction (Porter et al. 2024; USFR 2024). Because incarceration rates are still highly racialized, Black Americans are much more likely to be disenfranchised this way. In Southern states like Alabama, Florida, Kentucky, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia, more than one in seven Black Americans are disenfranchised because of felony convictions—twice the national average (Uggen et al. 2020). Without efforts to undo this vestige of slavery, felony disenfranchisement will continue to exclude millions of primarily Black and brown citizens across the South from civic participation.

Preempting local governance

Preemption is a practice where state legislatures bar local governments from adopting rules or standards distinct from those set by the state government. Over the last half century, preemption has been increasingly employed by majority-white legislatures in the South and Midwest to block local governments’ ability to enact ordinances related to labor standards, voting rights, climate, public health, law enforcement, and other issues.

Notably, in 10 of the 11 former Confederate states, localities are preempted from enacting local minimum wage ordinances. By prohibiting cities and counties from raising wages, majority-white state legislatures maintain a labor market dependent on a cheap and precarious workforce—an enduring feature of the Southern economic development model (EPI 2024; Blair et al. 2020; Childers 2024b).

In recent decades, the use of preemption has accelerated, targeting pro-worker measures like pro-union legislation, project labor agreements, prevailing wage ordinances, paid sick leave, and even the removal of Confederate monuments (Blair et al. 2020). This model, rooted in the legacy of slavery and exploitation, relies on suppressing labor rights and keeping wages low to preserve the economic dominance of a select few.

Conclusion

The preservation of the Southern economic development model has depended on the systematic disenfranchisement of Black and brown communities since emancipation. From the abolition of slavery through Reconstruction, the Jim Crow era, and even the Civil Rights Movement, the cycle of progress and backlash is testament to how fiercely and relentlessly Southern white elites will use racism, violence, and political suppression to secure their economic interests. Every step towards Black political empowerment has been met with new forms of suppression, aimed at maintaining a system that relies on an exploited and disempowered workforce.

Although this legacy continues through tactics like gerrymandering, felony disenfranchisement, and local preemption laws, periods like Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement, show that targeted policy action can dismantle racist barriers to voting and political participation. Breaking this entrenched cycle will require sustained efforts to dismantle the dynamic of political suppression and economic exploitation. Further, without confronting these deeply rooted structures of exploitation and disenfranchisement in the South, these dynamics will continue to spread and undermine progress across the nation.

“If you don’t organize the South, the South will come to you”

—Willy Woods, Unite Here Local 23 Chapter President

Notes

Economic Policy Institute, “Rooted in Racism and Economic Exploitation” (web page).

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP 2024; Brief of Amici Curiae Historians in Support of Appellees and Affirmance, Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP 2023.

Rucho v. Common Cause 2019.

Abbott v. Perez 2018.

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP 2024; Brief of Amici Curiae Historians in Support of Appellees and Affirmance, Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP 2023.

Alexander et al. v. NAACP 2023.

References

Abbott v. Perez, 585 U.S. ___ (2018).

Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, 602 U.S. ___ (2024).

Beaumont, Thomas. 2016. “AP Fact Check: Trump’s Bogus Birtherism Claim Against Clinton.” Associated Press, September 21, 2016.

Berzon, Alexandra, and Nick Corasaniti. 2024. “Trump’s Allies Ramp Up Campaign Targeting Voter Rolls.” New York Times, March 3, 2024.

Blackmon, Douglas A. 2009. Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II. New York, NY: Anchor Books.

Blair, Hunter, David Cooper, Julia Wolfe, and Jaimie Worker. 2020. Preempting Progress. Economic Policy Institute, September 2020.

Boustan, Leah Platt. 2017. Competition in the Promised Land: Black Migrants in Northern Cities and Labor Markets. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

Brennan Center for Justice. 2023 Voting Rights Restoration Efforts in Florida. August 2023.

Brennan Center for Justice. n.d. “Disenfranchisement Laws” (web page). Accessed August 26, 2024.

Brief of Amici Curiae Historians in Support of Appellees and Affirmance, Alexander v. South Carolina State Conference of the NAACP, 602 U.S. ___ (2024) (No. 22-807) 2023.

Cardon, Nathan. 2017. “‘Less Than Mayhem’: Louisiana’s Convict Lease, 1865-1901.” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 58, no. 4: 417–441.

Chen, M. Keith, Kareem Haggag, Devin G. Pope, and Ryne Rohla. 2022. “Racial Disparities in Voting Wait Times: Evidence from Smartphone Data.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 104, no. 6: 1341–1350. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01012.

Childers, Chandra, Dave Kamper, and Jennifer Sherer. 2024. “Operation Dixie Failed 78 Years Ago. Are Today’s Southern Workers about to Change All That?” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), May 14, 2024.

Childers, Chandra. 2023. Rooted in Racism and Economic Exploitation: The Failed Southern Economic Development Model. Economic Policy Institute, October 2023.

Childers, Chandra. 2024a. Breaking Down the South’s Economic Underperformance. Economic Policy Institute, June 2024.

Childers, Chandra. 2024b. The Evolution of the Southern Economic Development Strategy. Economic Policy Institute, May 2024.

Clark, Alexis. 2024a. “How Southern Landowners Tried to Restrict the Great Migration.” History, January 3, 2024.

Clark, Doug Bock. 2024b. “Election Deniers Secretly Pushed Rule That Would Make It Easier to Delay Certification of Georgia’s Election Results.” ProPublica, August 18, 2024.

Coleman, Kevin J. 2015. The Voting Rights Act of 1965: Background and Overview. Congressional Research Service, July 2015.

Darling, Marsha J. Tyson. 2024. “A Right Deferred: African American Voter Suppression after Reconstruction.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, July 3, 2024.

Democracy Now. 2022. “Native Americans Helped Democrats Carry Arizona in 2020. Now Their Voting Rights Are Under Attack.” YouTube video. Published November 8, 2022.

Desmond, Matthew. 2019. “American Capitalism Is Brutal. You Can Trace That to the Plantation.” New York Times, August 14, 2019.

Dirkson, Menika. 2024. “Convict Leasing in the Family.” African American Intellectual History Society, January 17, 2024.

Domonoske, Camila. 2017. “Trump Adviser Repeats Baseless Claims of Voter Fraud In New Hampshire.” NPR, February 12, 2017.

Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. 393 (1856).

Du Bois, W.E.B. 1935. Black Reconstruction in America 1860–1880. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2021. Unions Help Reduce Disparities and Strengthen Our Democracy (fact sheet). April 23, 2021.

Economic Policy Institute, “Rooted in Racism and Economic Exploitation” (web page). Last updated September 2024.

Economic Policy Institute (EPI). 2024. “Workers’ Rights Preemption in the U.S.” (web page). Last updated June 2024.

Engstrom, Erik J. 2013. Partisan Gerrymandering and the Construction of American Democracy. Ann Arbor, MI: Univ. of Michigan.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). 2018. Segregation in America. 2018.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). 2020. Reconstruction in America: Racial Violence After the Civil War, 1865–1876. Accessed, August 26, 2024.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). n.d.a. “On This Day, Apr 24, 1877: Hayes Withdraws Federal Troops from South, Ending Reconstruction” (web page). Accessed August 26, 2024.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). n.d.b. “On This Day, May 12, 1898: Louisiana Officially Disenfranchises Black Voters and Jurors” (web page).

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). n.d.c. “On This Day, Nov 09, 1866: Texas Legislature Authorizes Leasing of County Jail Inmates for Profit” (web page). Accessed September 11, 2024.

Equal Justice Initiative (EJI). n.d.d. “On This Day, Nov 22, 1865: Mississippi Authorizes ‘Sale’ of Black Orphans to White ‘Masters or Mistresses’” (web page). Accessed August 26, 2024.

Foner, Eric. 1993. Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction. Oxford, UK: Oxford Univ. Press.

Fowler, Stephen. 2021. “Georgia Governor Signs Election Overhaul, Including Changes to Absentee Voting.” NPR, March 25, 2021.

Franklin, John Hope. 1994. Reconstruction After the Civil War: Second Edition. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Frey, William H. 2022. A ‘New Great Migration’ Is Bringing Black Americans Back to the South. Brookings Institution, September 2022.

Gibson, Campbell, and Kay Jung. 2002. “Historical Census Statistics on Population Totals by Race, 1790 to 1990, and by Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, for the United States, Regions, Divisions, and States.” U.S. Census Bureau Working Paper no. POP-WP056, September 2002.

Gordon-Reed, Annette. 2011. Andrew Johnson: The American Presidents Series: The 17th President, 1865–1869. New York, NY: Times Books

Hannah, John A., Eugene Patterson, Frankie Muse Freeman, Erwin N. Griswold, Theodore M. Hesburgh, Robert S. Rankin, and William L. Taylor. 1965. Voting in Mississippi. United States Commission on Civil Rights, 1965.

Hulse, Carl. 2022. “After a Day of Debate, the Voting Rights Bill Is Blocked in the Senate.” New York Times, January 19, 2022.

Kelley, Erin. 2017. “Racism & Felony Disenfranchisement: An Intertwined History.” Brennan Center for Justice, May 2017.

University of Maryland (UMD), Hornbake Library. 2016 “Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Speech to AFL-CIO.” Special Collections & University Archives (blog). January 18, 2016.

Leadership Conference Education Fund (LCEF). 2019. Democracy Diverted: Polling Place Closures and the Right to Vote. September 2019.

Levine, Sam. 2024. “Georgia Election Deniers Helped Pass New Voting Rules. Many Worry It’ll Lead to Chaos in November.” Guardian, August 23, 2024.

Lewis, John, and Archie E Allen. 1972. “Black Voter Registration Efforts in the South.” Notre Dame Law Review 48, no. 1: 105–132.

Li, Michael. 2023. Alabama’s Congressional Map Struck Down As Discriminatory—Again. Brennan Center for Justice, September 7, 2023.

Li, Michael. 2024. Preclearance Under the Voting Rights Act (explainer). Brennan Center for Justice. March 11, 2024.

Litwack, Leon F. 1965. North of Slavery: The Negro in the Free States. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press.

Maye, Adewale A. 2022. “The Freedom to Vote Act Would Boost Voter Participation and Fulfill the Goals of the March on Selma.” Working Economics Blog, (Economic Policy Institute), January 13, 2022.

McCarthy, Justin. 2020. “Confidence in Accuracy of U.S. Election Matches Record Low.” Gallup, October 8, 2020.

Mississippi Civil Rights Museum (MCRM). 2024. “Mississippi in Black & White, 1865–1941” (web page). Accessed July 3, 2024.

Mississippi Department of Archives and History (MDAH). 2024. “The Mississippi Constitution of 1890 as originally adopted” (web page). Accessed August 29, 2024.

Mower, Lawrence. 2022. “Police Cameras Show Confusion, Anger over DeSantis’ Voter Fraud Arrests.” Tampa Bay Times, October 18, 2022.

National Urban League (NUL), Department of Research and Investigations. 1930. Negro Membership in American Labor Unions. January 1930.

Office of the Governor of the State of Alabama (OGSAL). 2024. “Governor Ivey & Other Southern Governors Issue Joint Statement in Opposition to United Auto Workers (UAW)’s Unionization Campaign” (joint statement). April 16, 2024.

Patterson-Payne, Jasmine, and Adewale Maye. 2023. A History of the Federal Minimum Wage: 85 Years Later, the Minimum Wage Is Far from Equitable. Economic Policy Institute, August 2023.

PBS. n.d.a “Southern Violence During Reconstruction” (web page). Accessed August 26, 2024.

PBS. n.d.b. “Murder in Mississippi” (web page). August 26, 2024.

Porter, Nicole D., Alison Parker, Trey Walk, Jonathan Topaz, Jennifer Turner, Casey Smith, Makayla LaRonde-King, Sabrina Pearce, and Julie Ebenstein. 2024. Out of Step: U.S. Policy on Voting Rights in Global Perspective. The Sentencing Project, June 2024.

Rucho v. Common Cause, 588 U.S. ___ (2019)

Rudensky, Yurij, Ethan Herenstein, Peter Miller, Gabriella Limón, and Annie Lo. 2021. Representation for Some. Brennan Center for Justice, July 2021.

Russ, William A. 1934. “Registration and Disfranchisement Under Radical Reconstruction.” The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 21, no. 2: 163–180. https://doi.org/10.2307/1896889.

Samuel, Terence. 2016. “The Racist Backlash Obama Has Faced During His Presidency.” Washington Post, April 22, 2016.

S. Exec. Doc. No. 40-53 (2. Sess. 1868).

Shafer, Ronald G. 2021. “The ‘Mississippi Plan’ to Keep Blacks from Voting in 1890: ‘We Came Here to Exclude the Negro.’” Washington Post, May 1, 2021.

Singh, Jasleen, and Sara Carter. 2023. States Have Added Nearly 100 Restrictive Laws Since SCOTUS Gutted Voting Rights. Brennan Center for Justice, June 2023.

Thornton, William. 2024. “Kay Ivey Says Alabama’s Economic Model Is ‘Under Attack’ with Auto Union Push.” AL.com, January 11, 2024.

Torres-Spelliscy, Ciara. 2019. “Everyone Is Talking about 1619. But That’s Not Actually When Slavery in America Started.” Washington Post, August 23, 2019.

Trump, Donald J. 2020. “Tens of Thousands of Votes Were Illegally Received after 8 P.M. on Tuesday, Election Day, Totally and Easily Changing the Results in Pennsylvania and Certain Other Razor Thin States. As a Separate Matter, Hundreds of Thousands of Votes Were Illegally Not Allowed to Be OBSERVED…” Twitter, @realDonaldTrump, November 7, 2020, 8:20 a.m.

U.S. Census Bureau. 1870. “Table I. Population of the United States—By States and Territories, in the Aggregate, and As White, Colored, Free Colored, Slave, Chinese, and Indian, at Each Census” [Pdf file], published 1870.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2024. “Table A-9. Historical Reported Voting Rates: Reported Voting Rates of Total Voting-Age Population in Presidential Election Years, by Selected Characteristics: November 1964 to 2020” [Excel file], published May 30, 2024.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR). 1968. Political Participation. May 1968.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (USCCR). 2018. Assessment of Minority Voting Rights Access In the United States. 2018.

U.S. Federal Register (USFR). 2024. Estimates of Voting-Age Population for 2023, 89 Fed. Reg. 22118–22119 (March 29, 2024).

U.S. Library of Congress (LOC). 1876. Radical members of the first legislature after the war, South Carolina. South Carolina, ca. 1876. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/97504690/

U.S. Library of Congress (LOC). 1882. The Congressional Districts of South Carolina as “Gerrymandered” by the Democracy in 1882. Map. https://www.loc.gov/item/2015588077/

Uggen, Chris, Ryan Larson, Sarah Shannon, and Arleth Pulido-Nava. 2020. Locked Out 2020: Estimates of People Denied Voting Rights Due to a Felony Conviction. The Sentencing Project, October 2020.

United States Congress, Senate (USCS). 1865. Message of the President of the United States. Washington, DC, 1865. Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/2022699613/

Ura, Alexa. 2021. “The Hard-Fought Texas Voting Bill Is Poised to Become Law. Here’s What It Does.” Texas Tribune, August 30, 2021.

Vasilogambros, Matt. 2024. “New Voter Registration Rules Threaten Hefty Fines, Criminal Penalties for Groups.” Stateline, June 7, 2024.

Waxman, Olivia B. 2022. “The Legacy of the Reconstruction Era’s Black Political Leaders.” Time, February 7, 2022.

Widra, Emily. 2024. States of Incarceration: The Global Context 2024. Prison Policy Initiative, June 2024.

Williams, Jhacova. 2020. “This MLK Day, Remember Emmett Till and Voter Suppression.” Working Economics Blog (Economic Policy Institute), January 16, 2020.

Wills, Matthew. 2019. “Racial Violence as Impetus for the Great Migration.” JSTOR Daily, February 6, 2019.