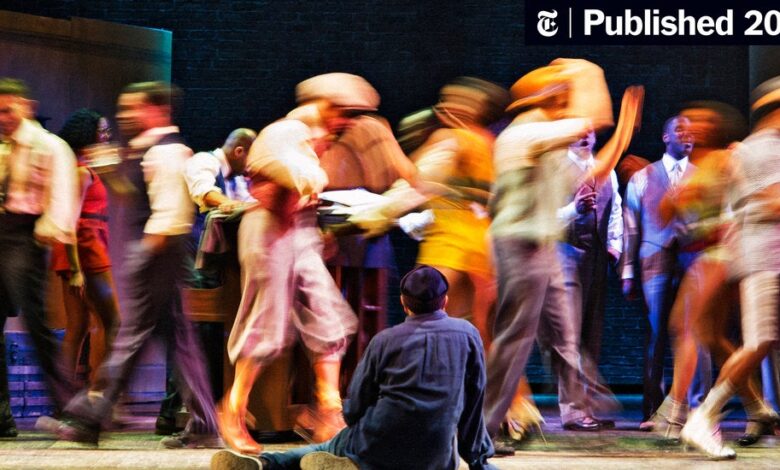

‘Shuffle Along’ and the Lost History of Black Performance in America

Ninety-five years ago in New York, a journalist named Lester Walton bought a ticket to see a much-buzzed-about new show, a “musical novelty” that had opened about a week before at the Sixty-Third Street Theater. Or the Sixty-Third Street Music Hall, as it was more properly called. A kind of multipurpose performance space, not very big, not very nice, “sandwiched in between garages,” Walton wrote, and “little known to the average Broadway theatergoer.” You could rent the place for the night. It had philosophical lectures, amateur violin recitals and religious meetings, and during the day it showed silent movies: “ ‘Pudd’n Head Wilson,’ with Theodore Roberts, tomorrow.” But on this evening — and for many months to come, as it turned out — the stage belonged to an all-black show called “Shuffle Along,” a comedy with lots of singing and dancing. A problem: The music hall had no orchestra pit, and this show needed an orchestra. It needed space for the band, which happened to include a 25-year-old musician known as Bill Still, later to become the famous composer William Grant Still, but in 1921 a mostly unheard-of young man from Arkansas, switching among the six or seven instruments he taught himself to play. The production was forced to rip out seats in the front three rows to make room. These were people used to improvising. Among themselves, they referred to the show as “Scuffle Along.”

Les Walton, the journalist in the audience that night, was also a theater man. In St. Louis, a city he left behind 15 years before — and where he got his start as America’s first black reporter for a local daily, writing about golf — he had somehow come to know and collaborate with the legendary Ernest Hogan, a.k.a. the Unbleached American, an early black minstrel and vaudeville comedian who (by some historians’ reckoning) was the first African-American performer to play before a white audience on Broadway. Walton and Hogan wrote songs together, and it was Hogan who first brought Walton to New York, as a kind of business manager. Hogan was not so much unbleached as the opposite of bleached. He was a black entertainer who painted his face — with burned cork or greasepaint (or in emergencies, lampblack, or in real emergencies, anything black mixed with oil) — to make it appear darker. Or at least to make it appear different. In one picture of Hogan, from the 1890s, he looks more like a sock puppet, wearing a clownish pointed cap.

The blacks-in-blackface tradition, which lasted more than a century in this country, strikes most people, on first hearing of its existence, as deeply bizarre, and it was. But it emerged from a single crude reality: African-American people were not allowed to perform onstage for much of the 19th century. They could not, that is, appear as themselves. The sight wasn’t tolerated by white audiences. There were anomalous instances, but as a rule, it didn’t happen. In front of the cabin, in the nursery, in a tavern, yes, white people might enjoy hearing them sing and seeing them dance, but the stage had power in it, and someone who appeared there couldn’t help partaking of that power, if only ever so slightly, momentarily. Part of it was the physical elevation. To be sitting below a black man or woman, looking up — that made many whites uncomfortable. But what those audiences would allow, would sit for — not easily at first, not without controversy and disdain, but gradually, and soon overwhelmingly — was the appearance of white men who had painted their faces to look black. That was an old custom of the stage, going back at least to “Othello.” They could live with that. And this created a space, a crack in the wall, through which blacks could enter, because blacks, too, could paint their faces. Blacks, too, could exist in this space that was neither-nor. They could hide their blackness behind a darker blackness, a false one, a safe one. They wouldn’t be claiming power. By mocking themselves, their own race, they were giving it up. Except, never completely. There lay the charge. It was allowed, for actual black people to perform this way, starting around the 1840s — in a very few cases at first, and then increasingly — and there developed the genre, as it were, of blacks-in-blackface. A strange story, but this is a strange country.

Ernest Hogan died not too long after bringing Les Walton east to New York, but Walton maintained his interest in the theater and songwriting and had managed a theater in Harlem, the Lafayette. A progressive theater — it was the first major venue in New York to desegregate its audiences, i.e., to let blacks come down from the balcony and sit in the orchestra seats — and Walton worked hard to put serious black theater on the stage. At the same time, he had been making a name for himself as one of the first black arts critics in America, writing for The New York Age, a black newspaper. (His life would get only more interesting — over a decade later, Franklin D. Roosevelt named him an American minister to Liberia.) That evening, he went to see “Shuffle Along” on assignment. It was late May. That week, the Tulsa race riots had erupted more than a thousand miles away. A white mob torched one of the most prosperous black neighborhoods in America.

Source link